A home is where we feel the most at ease, whether it is through the good times or the bad. It is a moment of solace in an otherwise breakneck pace of life. And for a country as vast and highly populated as India, the housing conditions of its residents will always be a matter of utmost importance. Even though its definition varies across the country, the meaning of the word shelter boils down to one thing. A shelter is the primary need of any human being. It is a prerequisite for survival and living a dignified life. Hence, it was astonishing when the Census of 2011 put the number of homeless people in India at 1.77 million.

This number was a direct product of a fast-rising population post-independence and rapid urbanization in nodes across the country, thus making it challenging for any government to meet the housing needs of all. The 1985 Indira Awas Yojana attempted to tackle this issue and successfully achieved its targets for the rural areas. Currently, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), introduced in 2015, is further improving upon the same under its “Housing For All” program.

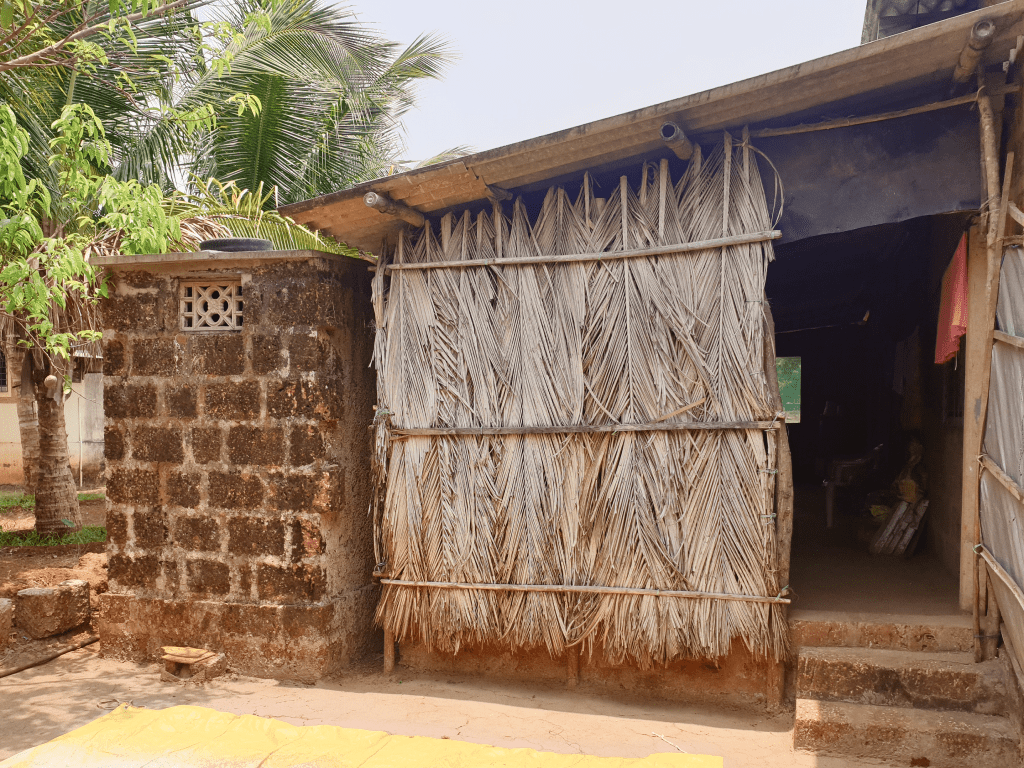

Schemes such as these brought to light that homelessness was just one of the factors that created a housing deficit in the country. Many people lived in shelters that could not be called adequate. Thus, the first step to resolving the housing deficit in India would be to take a closer look at the factors contributing to it. Housing shortage or housing deficit is a broad term that, along with homelessness, also includes forms of housing or shelter that are not ideal for people to lead a healthy, comfortable life. 9.6% of the country’s population lived in kutcha (temporary) houses as of NSS 69th Round, while an additional 24.6% lived in semi-pucca houses. A kutcha house is one made of clay, bamboo, unburnt bricks, or any material that is not durable, with a roof made of flax, grass, crop residue, or bamboo. A semi-pucca house on the other hand has walls made of solid material but frigid and non-durable roofing. People who live in these shelters are often vulnerable to natural calamities and seasonal challenges such as excess rainfall or heatwaves. The dwelling units require constant repair to be habitable. Provision of basic amenities such as water, sewage lines, and electricity also becomes difficult. There is an overall deficit in the standard of living in such housing.

These problems repeat themselves when we consider dilapidated housing units as well. They are highly unstable and dangerous to live in and lack appropriate connections to the newer structures around them. Shelters such as these are often spaces of risk, further adding to the problems of its inhabitants. One of the ways to tackle these issues has been to rehabilitate the residents of such structures while repairing or repurposing the dilapidated spaces on an urgent basis. Dwellings that are poorly or illegally built and thus not adhering to safety standards anymore come under this issue.

In urban areas, the problem of housing congestion goes hand in hand with dilapidated shelters. As the rural population moves towards cities, there is a drastic shortage of land to construct affordable shelters. A city can only hold a limited population before its resources start depleting faster than they get replenished, and land is a resource that is difficult to reclaim. This leads to informal settlements in pockets of urban spaces that are not demarcated for a specific use. Its residents make peace with the poor living conditions in exchange for better job opportunities, thus falling into a cycle of inadequate conditions.

In rural areas, there is a different problem. 40% of households did not own land as per the 58th round of the NSSO. Building a house without land is the first challenge that the people in rural India face. On top of that, it is difficult for the economically weaker sections to maintain kutcha or semi-pucca shelters, often because natural calamities are more likely to strike in the rural areas of the country than in cities. Improperly built shelters suffer heavy damage. For an already struggling homeowner, repairs after every season make it difficult to save enough to build a pucca house or buy land. To put it simply, someone who can afford footwear from a good brand can use the same for years, but others who can only afford cheap footwear will be stuck in a cycle of buying new ones after every season, eventually never allowing them to be able to afford something good. Thus, they are not able to break out of this cycle. This makes it important to include such shelters in the housing deficit so that individuals can focus on improving other aspects of their life.

Housing is the most basic need in any society, and complications differ depending on where you look under a microscope. Houses are important social and cultural hubs as well. What goes on around the house is as much affected by it, as how the house itself interacts with its context. It is a vast network of systems and resources that work together to make a person comfortable. A dearth in any or all of them immediately brings down the standard of living for an individual. Improper water supply is disruptive to the basic functioning of the household. Work-life is affected by the timings of water availability, thus making it more difficult to rise out of it. Lack of electricity can hamper access to educational resources or just the ability to study in a safe space. Improper sewage and sanitation is a general hazard to overall health, and so is the lack of a waste management system. These are conditions that make it difficult for anyone to live a comfortable, healthy life. Tackling its root cause by the provision of a better shelter to the requisite population thus becomes imperative.

With the spread of Covid-19 in the past 2 years, many have been forced to re-evaluate the kind of spaces that they are living in. Housing is not just about what happens inside the dwelling unit, but also about what happens around it. A space that allows its communities to flourish while providing more than just the basic needs is ideal. With current habitation patterns, it became glaringly evident that urban development had slowly failed at providing this to everyone. This has led to a wave of re-migration to villages and small towns. With access to communication facilities, rural life provides much more leg room for a comfortable living than cities. This could lead to a shift in the housing situation of the country.

Keeping in mind these observations, Visava realizes that architecture as a fraternity needs to be more accessible to this vast number of people. It is not enough for a person to have four walls with a roof on top as their shelter. Everyone deserves to live in a home designed to their needs if not wants. All they need is a platform that can help them achieve this. Visava aims to reach out to these people and provide them with an amicable solution while keeping in mind all the restraints. It would work with the propagators of different housing schemes in the country and make sure that it is not just Housing for All but also good housing for all through good design.